It's a sunny Sunday afternoon —celebratory day: the sun hadn't visited your city's sky in ages— and you're out in the flea market. Browsing the offerings among the throng of people: old things, new ... [+]

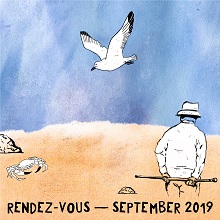

Chekhov, the Old Man, the Seagull and the Crab

Also available in

ItalianThe old man is watching a seagull eviscerating a crab. The decapod crustacean probably was handsome in his youth but not any longer. Does he wish he could scream? Or is it better to be stoic and swallow your pain?

The old man sits on a park bench, facing the beach. His right hand rests on a gentleman's walking stick. There is half an American silver dollar embedded in the nob. Very patriotic. Immigrants better be patriotic or else.

He's not ready for a cane, let alone a walker.

The old man is a writer. He tells everyone on social media that it's easier to write in Russian than in English because the Russian alphabet has 33 letters while the English has only 26. More choice is better. He knows. He writes in both. He's not Chekhov in either, but he's trying.

The old man gets up and stumbles along the beach, among the dog walkers, joggers, mothers and occasional fathers pushing strollers. The strong breeze inflates the sails of the pleasure boats and tries to blow off the old man's cap. It's not strong enough yet.

The old man is still working. Earlier today, in his line of work, he listened to an old woman who refused to get palliative care for her husband. "He's not a vegetable," she kept saying, pointing her knobby finger. "See, he can move his hands a little."

The palliative nurse smiled like a funeral home director. In the end, the nurse won. Because the patient has no choice but to die, this kind of nurse always wins, just like the directors.

The old man comes to the edge of the water now, examining the mortal remains of the crab. The crustacean is not a vegetable either. He's just dead. He skipped the intermediate stage and proceeded to the exit. The seagull is watching the old man out of his malevolent, golden-yellow eyes. He's the king of the beach. He probably doesn't eat vegetables. He's quite an intelligent bird. Prophetic even. Like in Chekhov's "The Seagull," there is a love-hate triangle here: the old man, the seagull and the crab.

At their parents' home, the old man's grandkids ask him serial, circular questions.

"Why are you so old?"

"Because I was born a long time ago."

"Why were you born a long time ago?"

"Because my parents married a while back."

"Why did they marry a while back?"

"They wanted to get married while they were still young."

"Why did they want to get married while they were still young?"

"They wanted to give birth to me."

"Why did they want to give birth to you?"

"So you will have someone to answer your questions."

The old man is wishing he could resurrect the crab. He'd like to touch him with his walking stick and have the crab grow flesh again and run for the water. If that were to happen, the old man would try tomorrow to touch the husband who is not a vegetable with his stick. After all, prophets and kings healed with their bare hands. They didn't have a gentleman's walking stick with half a patriotic silver dollar embedded in the nob. Modern tools are hard to beat. Every writer but the Luddite knows that.

The old man can even mumble a charm in two languages to amplify the effect. Everyone says his accent is charming. Charming. He laughs at his own pun.

He touches the crab with the tip of his stick and says his charm. The crab is still dead.

The old man is walking toward his car. He has to answer more serial questions. The seagull stares. He knows. Not everything, but only what he needs to know. And that's enough. The old man, with his back to the sea, can't see that the crab comes alive now, but the seagull can.